The Person of Art Lazaar

by Art Lazaar

The view from the inside: the first-person character tells how it is.

In his current work-in-progress, my author, Kevin Price, decided to write me in the first person, a new experience both for him and me. This essay explores a little of what it means to be written in the first person, in a narrative with alternative third person points of view.

The Balsamc Jihad is a story which somehow got me involved right at the centre; I’m the protagonist, the main man, and oddly enough, I’m also the storyteller. Well for some of it. There’s an awful lot about the circumstances of The Balsamic Jihad of which I knew absolutely nothing when the events were unfolding and, even were I to tell it in hindsight, there’s much I couldn’t tell you: my reportage would be unreliable. This story is full of political machinations with such levels of secrecy that I’d have to have the resources of the NSA just to tell you that they were happening, let alone find out what was going on behind those closed doors. It seems, though, the villain of this piece, Roger Lamord, does have that kind of surveillance technology at his fingertips. Yet all Kevin gave me was a tenuous academic career and a poxy Poetic License — a secret document that failed utterly last time I used it, so I’m quite sure you will understand that it gives me pause to even contemplate trotting it out again. It’s not much chop against the skills of an Edward Snowden type.

Yet this is the kind of battle I’m forced to undertake. And for what? Well, it’s to solve a murder and to prevent another happening, but what I discover in the process is something far more sinister, something that will shock you to the core when you see the lengths to which some people will go to get what they want. And for reasons he chose not to share with me, Kevin decided to cast me in my own voice. I’m guessing, of course, that it was to reduce the fictive distance between you and me, so that what you get from me is the truth — at least the truth as I see it. Perhaps he thinks you will find the events more plausible because he’s getting me to tell it directly to you rather than convey my actions and thoughts in a more omniscient manner.

One of my main concerns is that, even though I can tell you what happened to me as I got sucked into this deplorable mess, I can’t tell you what was happening in other parts of the storyworld, because I wasn’t there. So those events, for example the events that occur within Lamord’s private world, Hunter’s or Boulter’s, are not within my purview and Kevin has chosen to write those scenes employing an omniscient narrative position, but always within the point of view of one of those central characters, bringing to bear a range of narrative perspectives that we will discuss below.

While it is commonly considered ‘not conventional’ to chop or drift between what we know of as the first person and the third person narrative voice, it is certainly not without precedent. Two contemporary writers who make excellent use of the technique writing within a similar genre to The Balsamic Jihad are Michael Connolly with his Jack McEvoy novels, and James Lee Burke with Dave Robicheaux. And Kevin’s good friend, James N Frey, argues quite soundly in How to Write a Damn Good Novel II, that there is nothing the writer can do with a third person point of view that he can’t do in the first person.

However, were I to tell you what happened in the opening scene where Hunter takes the girl under his wing, I could only tell it as perhaps Hunter told it to me. Which, of course, means that Hunter would have had to tell me, and he would have to tell me all of it. But Kevin’s problem is more complex. He is placing a temporal dimension on the events of the story, he wants you to see things as they happen, not be told about them after the fact, which is the only way I could do it. So, while Jim Frey is mostly correct, he is not completely correct. To tell a story that requires the reader to be cognisant of certain facts in ‘real time’ means the reader must have access to the events as they happen. The best solution is most likely to be all points of view in the third person. So why has Kevin chosen to write me in the first person?

Who is this ‘person’ anyway?

What we are talking about here is the persona of the one who tells the story and the shift from it being me, as ‘I’, to a pseudo-character accessing the mind and thoughts and the viewpoint of Kelly Boulter, Roger Lamord or Hunter as ‘they’. However, I am not a real person. I’m a Homo Fictus — a fictive invention created in the mind of my author, given a voice and an opinion and a position relative to the events of the story, which quite naturally (although you probably wouldn’t notice it especially) places me in a position relative to you.

I am not Kevin Price, the author, and I don’t represent him, and he does not speak for me while I am telling you what happened. Nor does the pseudo-character voice that fills in the details of the story in scenes where I’m not present belong to Kevin Price. Kevin Price is a real person, he is the author of The Balsamic Jihad, and in order to narrate the story, he has taken on two different personae — the one you will read as ‘I’ (i.e., me) and the one you will read as ‘them’, observing the action from varying degrees of an omniscient perspective. You, the reader, will perceive an ‘idealized projection … not the real person.’ 1

Our most common way of discussing the idea of the narrative voice, turns on whether that voice of the narrative is either projected from within a character, or projected upon a character. We call the former, the First Person, and the latter, the Third Person — in either case, however, it is, as James N Frey suggests, an ‘idealized projection’. It’s not real people speaking.

Gerard Genette argued that the terms of ‘person’ are misleading and inaccurate. He says that ‘only a subject can narrate’: 2 that is, someone who has an active role in the story. When an author relates the events using a third person narrative, he is creating a pseudo-character to fill that role, which Genette labelled heterodiegetic, while he labelled a narrative role such as mine autodiegetic (which in all truth sounds like a formidable disease). Were I not the protagonist, my role as narrator according to Genette would be homodiegetic. Oxford dictionaries explains diegetic as an adjective pertaining to diegesis, a Greek word meaning narrative, which adopted by the French came to refer to ‘The narrative presented by a cinematographic film or literary work; the fictional time, place, characters, and events which constitute the universe of the narrative.’ 3 In a far more complex and less comprehensible way, Genette is simply saying what Frey has told us, that the author will either tell the story with a narrator projected from within a character — either the protagonist or another character — or with a narrator projected upon many or other characters; a pseudo-narrator accessing the range of points of view.

Point of view is simply the position from which events are being observed. It includes what can be observed through the senses, and it includes what is excluded from that given perspective. And quite often it is what is excluded that guides the choice of who is telling the story at a given moment. Point of view is one of the author’s most effective tools for creating suspense, by which your perspective is manipulated through the eyes of particular characters involved in order to facilitate your orientation to the story, its core conflicts and its complex story world. This manipulation is, in effect, the author providing you a position from which you can take an active part in that ‘idealized projection’. A position of perspective.

In every story there is an unwritten contract of understanding between author and reader — between teller and hearer — which holds that the author will deliver to the reader a particular kind of package, and in some respects, the decision of narrative voice is heavily influenced by the kind of package promised. Different genres of writing call for particular stylistic decisions to be made because that is the way the reader expects them. Yet, through the ages, authors consistently modify this contract, and readers come to embrace the modifications — in some cases they even get used to it and expect it in that author’s continuing canon.

In the case of The Balsamic Jihad, Kevin’s decision was propelled in part by the genre choice. This is a political thriller, a noir fiction, set against the backdrop of the real event of the 2013 Australian Federal Election. But the circumstances of the fiction are, well, all made up if I’m honest, as is the complete circuitry of characters — me included. The probability of the fiction, however, arises from certain events that were imagined to have been carried out in utmost secrecy specifically directed to influence public opinion and thereby the voting outcome.

A thriller, as you may be aware, is a story which has at its centre a conspiracy to turn the world toward an ideology espoused and pursued by a villain. The villain is trying to effect a change that will have a deleterious effect on the world of the hero. As Jerry Palmer says in Thrillers: genesis and structure of a popular genre, ‘The excitement every thriller reader demands is the moral sympathy accorded the hero in his struggle against evil, it is seeing things through his eyes.’ 4 Which, of course, means you must be able to see things through my eyes and be sympathetic to my moral dilemma.

In an odd twist of circumstances, I am caught up in this conspiracy somewhat indirectly. It transpires that, in an effort to protect the secrecy of their operations, the conspirators have committed a murder. But they are potentially facing exposure from a young woman who is the sister of the murder victim. She is an asylum seeker from Iraq, and has escaped a dreadful community detention, an escape which, apparently, threatens the conspirators and they want to find her, presumably — or at least, I presume — to send off to the same destination as her brother. It becomes my job to hide her and keep her safe from this terrible end, which may or may not be the truth.

But of course, I cannot simply stop at that. It is written into my DNA that I must enter the world of the conspirators in order to remove the threat altogether against the young woman I am charged to protect. To do that, I must bring to account the murderers of her brother, something which the local police detectives are struggling with — not least because they have no way of identifying the victim, but also because of the levels of corruption that shield the real culprits and inhibit effective investigation. This is a complex paradox emerging from a paranoid world and involves extraordinary wealth, high political power, competent but impotent police power, a secret but frequently fallible license to act outside the law, and the challenges of social invisibility. It’s a crucible that at times reaches unbearable temperatures all in an attempt to secure freedom.

Kevin’s decision to give you direct access to my view of the world as I stumble through its mists is a technique he is using to heighten the sense of drama, particularly when it is juxtaposed against more objectively observed drama involving situations beyond my access. He presents this world from two perspectives: the one that you might project on to me as the outsider involved in bringing down a powerful conspiracy, and the other that you might project onto the dichotomous worlds within which Roger Lamord and Hunter move, or the balancing pole held in the hands of Kelly Boulter. It is from these vantage points you will be able to gauge my moral position and lend it your sympathy. As events unfold you will feel the pincer pressure of the conspiracy acting on me because you learn things that I don’t know, or before I get to know them. This ‘knowledge advantage’ lets you weigh up the evidence I am trying desperately to gather. From my perspective, the world is forever opaque and I am forced to act on hunches and half-baked ideas that more often than not run afoul of the proper course of action, which you can see clearly. You see me first hand making these mistakes, but you are not in a position to correct my course. You will be frustrated, enraged and sometimes wish you had a gun to my head.

Perspective — not all you see

The modern novel, according to Robert Weinmann ‘is born of its narrative perspective.’ 5 The point of narrative perspective is a troubling aspect of point of view. Weinmann is telling us that neither the writer nor the reader can be removed from the social and political influences of their time. The orientation, the language and the point of view is governed by them, as is the author’s knowledge and the reader’s contextual understanding. What we have to account for is a lag time between the act of the writing and the opportunity of the reading — what Kevin, in some of his other theoretical work, calls the ‘reader opportunity gap’. The wider the reader opportunity gap, the more respondent nostalgia comes into play and the more you, as respondent, will imagine the social and political circumstances of the author, so that you might equally imagine the circumstances of the characters and the narrator. The narrower the gap, the less you rely on nostalgia and more on contemporary commentary to provide you with the context that produces the fictive dream.

All this goes to say, of course, that your point of view (as respondent) is just as important as those of the narrative characters within the story. The society we move in affects the way we see the world. My job is to help you see a particular world with a morally corrupt society, built on contemporary events, from which you reach a conclusion — an understanding that ‘the truth alone does not set you free’. Our social and political influences each have their truths, and frequently those truths, as you can see from our different world views, are contested.

In The Balsamic Jihad you will be immersed into four quite different world views. Roger Lamord’s view is a perspective afforded only to those of extreme wealth and influence in which people enjoy privilege and freedoms of movement that most of society are unable to experience. Hunter’s is that of the homeless man in fear for his life, a man living on the street, completely powerless for whom freedom is both a distant memory and a wistful goal. Detective Sergeant (acting) Kelly Boulter’s is that of the police officer frustrated by a misogynistic work environment and thwarted advancement prospects, and the hangover of a previous failed investigation that left the relationship between us at a low point. My world view is that of the idealist, the academic who loves to teach but hates the limiting pressure of the institution, the ex-journalist who believes you have the right to tell your story simply because it happened to you, the poet whose challenges of the authority of society have produced a bitter cynic, and the holder of a Poetic License — an all but worthless piece of paper that licenses me to enter the murky space somewhere between the law and the lawless and to apply my dispensation for poetry to enjamb the wrongdoings of corrupt officials and bring them to justice.

Although, according to thriller lore, I am supposed to be both sexually potent and sexually isolated, I am in fact sexually flawed: I’m charming but licentious, a notorious recalcitrant whose three prior marriages have all ended acrimoniously and left me with a bitter and distorted view of how relationships should actually work. (And these are just my strengths.) This, quite naturally, causes me a lot of grief and distorts my world view to the point where it affects my ability to fit in. Even though I am, as Palmer puts it, ‘the everyman participating fully in the life of the community as a professional …’ 4 and am, in fact, very good at my job, I remain intrinsically a loner. This is something of a paradox, and when you get to see the world from my point of view, which is a different experience of how you see it from Lamord’s, Boulter’s or Hunter’s, you will understand my particular psychosis, and how it keeps me isolated.

Each of the world views in The Balsamic Jihad are influenced by the overall social and political environment from within which it is created. There is a looming and desperate election campaign, there is conspiracy afoot to influence the way voters will lean, a murder has been committed to protect the conspiracy, an escapee threatens the security of the conspirators, the cops are at a dead end, and (to them at least) I am persona non grata. The contested mysteries include the identity of the murder victim, the identity of the murderers, the whereabouts of the girl, the power of my Poetic License, the levels into which official corruption reaches, and of course, whether, in the end, I will be able to clarify the mysteries and eliminate the threats.

Dimension, distance and intimacy

Perspective is the way we see multi-dimensional objects or actions in a limited dimensional space so that the full extent of their physical properties are understood both in their magnitude and their relationship to the circumstances and the circuitry of characters. In your response to the work, you experience perspective through the projection of the point of view available to you, along with the accumulated knowledge you bring to that moment. Your mind is seeking the whole story, you want to see how all the disparate parts fit together to make a whole, and how the core conflicts are resolved. You are actively seeking an understanding. My job is to keep information from you, to misdirect your attention and intrigue so that you question what I see as my reality, and enable you to gradually see how the intricate web of mystery became so entangled, why it is important, and how, through my particular skills and tenacity, it becomes unknotted, at which point you will have a complete understanding of what I went through and why. The other characters in the circuitry may not appreciate what I do, but you will.

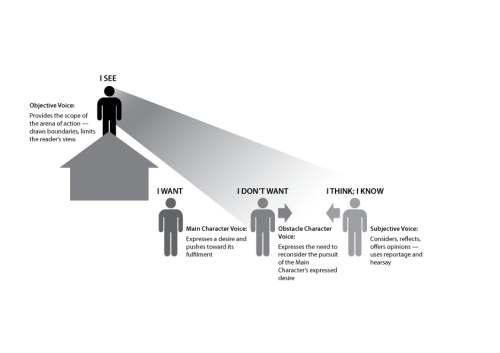

When we are talking about perspective we are considering our positions relative to each other, relative to the other characters and relative to the action. The point of view you experience is conditioned by this entanglement of relationships, and where you stand in respect of where the point of view character is at any given time. At times you will find me so intimate, you’d think we were sleeping together (I did warn you!), and at other times I will be so distant as to be a mere speck on your fictive horizon — you’ll be wondering where I got to. On an altogether different, but equally dependent axis, your experience of the action will, at times, be highly subjective, while at other times, Kevin will objectify the characters and their business, pushing them into the distance so you can breathe freely and relax momentarily. The movement of point of view from internal to external viewpoints will be, for you, something of a roller coaster ride.

We are all affected by the different aspects of perspective — by all I mean me, the other characters and you — our elevation, for example may be conditioned in a physical, social or psychological dimension. There will be times the viewpoint I offer you will be a lofty one, such as when I’m in the office of my dean at the university, at other times, particularly in some scenes with Hunter, we’ll be on the lowest social rung available. There’s a scene with the newly appointed dean of my school, for example, where you will be wanting distance because I come across as sleazy and lascivious, and Kevin is refusing you, forcing us to be close enough for you to feel not a little repulsed. But at another time, when I am sharing a meal with Hunter in a soup kitchen, the intimacy will prick at your social conscience because you find it difficult to reconcile your values when you experience life at its most hopeless. You will have no choice in these matters because these are the extremes you need to experience in order to understand my revulsion of institutional command and control, and the powerlessness we all have to act against it.

The third person points of view Kevin gives you will include moments of ‘free indirect speech’ where you will get a real sense of Lamord’s, Boulter’s and Hunter’s thought processes, but he will also provide you with wide angle and long distance views at other times. There will be times when my own point of view will have different angles involved: I may see something from an acute angle, but report on it negatively to you. There will be different lenses applied that will cloud my view, refocus it, adjust its depth of field, filter…. You may have seen the same thing at a different time from another character, and have a positive view of it. Kevin gets excited when he plays with aspects of perspective and causes conflict between us — other characters and me. And curiously enough, between you and me too, which is one of the great advantages of using a point of view shift: it puts you and me on the same page.

The Balsamic Jihad is a complex story. The central issue at stake is freedom. A murder event sets the stakes at life and death from the start. One reason that Kevin’s decision to write me in the first person troubles me a little is because it exposes me, it strips me bare — I can’t hide behind an objective narrative viewpoint the way Boulter and Lamord and Hunter can. I have to declare my hand to you at all times, whereas they each enjoy protection from the frightening aspects of having to convince you that I represent the moral high ground, even in my most despicable moments. If I fail to convince you of that, and I’m behind to begin with, I will fail to show you that we need more than truth alone to reach freedom.

Lamord, as I’m sure you will discover, is a charming man, very wealthy, very powerful, very influential. He can have anything he wants — anything. All he need do is snap his fingers. I’m convinced he will charm you, and that could place me and my credibility with you in a precarious position. I’m sure he will find ways to discredit me that haven’t yet been heard of. Had Kevin chosen to write me in the third person, I wouldn’t have this concern because it would then be up to the pseudo-narrator to present a balanced view, and in that situation, the narrator’s reliability can readily be called into question. As it stands, my credibility is on the line from the start.

A balancing act

How does Kevin expect to get a balanced view then? It’s quite simple, really. To start with, someone has to provide the objective viewpoint, the view from the top, from where you can see everything. As the story progresses, this viewpoint will be increasingly provided by you, yourself, with knowledge and conclusions you gather along the way. An initial understanding of our locale, the time and seasonal impacts will afford you a view of the challenges of life at the very bottom of the food chain. When I come along, I will show you a little of my character, and give you some insight to my history and my connection to Hunter, and you will see how I become embroiled in this sordid little affair. When you meet Lamord, you are protected from all of the extremes. You will see how he has risen to where he is today, and what keeps him there, what forms his beliefs and sense of morality and how he maintains a considerable moat between him and the lower echelons of our society. With Kelly Boulter, you will get a sense of the great difficulties ethical officers with our police services face and the challenges they encounter when they are forced to delve into dilemmas that may cost them their careers, if not their lives. When you are next oriented within one of the viewpoint character’s spaces, you will bring with you a sense of what already exists. Small details will help you add to that overall picture; your sense of how they (and me, I guess) are seeing things will gradually develop. By the conclusion, the objective viewpoint will be yours entirely and it will be how you see the disparate threads of this sorry tale come together.

Generally speaking, the scene of the moment will be played in the main character’s viewpoint. In scenes that involve me, that will, of course, be yours truly. This is your close personal view of what is actually happening at that moment, you will experience the challenges that I face (or Boulter or Lamord or Hunter) based on your understanding of what I want, and the contests I face in order to get it, and the mistakes I make that you would like me to avoid. You will feel my paucity of feelings and understanding, and see my missed opportunities to correct those deficits; you will rail against my exuberance in strength and order, and implore me to be more reasonable, less rash, more sensitive to my surroundings. All of this comes because you will carry with you an overall objective viewpoint and set that off against my personal viewpoint as main character.

While The Balsamic Jihad is primarily a contest between me and Lamord, I have to pay homage to Hunter as the instigator and mentor character, and Boulter as the foil, the contagonist who resists my involvement and therefore forces me into decisions that I might have otherwise made differently. She is a talented detective and forensics scientist, dogged in her pursuit and formidable to me. While somewhat limited, Hunter has a vital role to play as a guardian character and keeper of the moral chalice. In any scene that involves any one of us, you will also encounter the obstacle character viewpoint. This is similar to the main character viewpoint, but taken from the perspective of the obstacle character in that scene — who is anyone standing in the way of progress, not just Lamord. In any scene involving me and any other character standing in the way of my progress, Kevin must maintain the balance by ensuring that my viewpoint as main character, is set off against the other’s viewpoint as obstacle character. You must be able to make a judgement about the conflict of the moment and its moral contribution to the story’s progress, and that is only possible if you are in a position to weigh up the opposing viewpoints.

This very close encounter between the main character and the obstacle character viewpoints produces yet another experience that Kevin identifies theoretically the subjective viewpoint, which places you right within the action, showing you the course that the scene takes. It is from this position that you will form judgements about my morality and Lamord’s morality, particularly as it is illustrated by Boulter and Hunter. It is from here you will sense the inevitable change, the turning point, the transformation and the forces that generate it: the story’s objective correlative.

I admit I’m somewhat ambivalent about my feelings toward this. Being written in the First Person gives me a status I have not previously enjoyed, and moreover, it gives me a status that contests Boulter’s, Lamord’s and Hunter’s. While Boulter and Lamord are both new to this, Hunter has enjoyed a previous pre-eminent position, and to be ‘one up’ on him is actually something I should relish. However, I do feel also, it may have been easier to do my job were I given the greater autonomy that comes with being written in the Third Person. But then, that’s pure speculation, and I’ll leave that to the critics to ponder.

I’ll see you on the pages.

- James N Frey, How to write a damn good novel II, St Martin’s Press, New York, 1994. Page 79. ↩

- Quoted in Susan Sniader Lanser, The Narrative Act, Princeton University Press, New jersey, 1981. Page 158. ↩

- Oxford English Dictionary Online, accessed June 2014. (http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/52402?redirectedFrom=diegetic#eid6741737) ↩

- Jerry Palmer, Thrillers: genesis and structure of a popular genre, Edward Arnold, London, 1978. Page 82. ↩ ↩

- Quoted in Susan Sniader Lanser, The Narrative Act, Princeton University Press, New jersey, 1981. Page 108. ↩

[…] The Person of Art Lazaar […]